We need to take a hard look at our ring roads in our cities because they have become safety hazards, are poorly implemented, and have contributed to unplanned growth around them.

As the city grows and traffic increases, the first response from administrators is to build a ring road. And when the first ring road gets absorbed into the expanding city, the demand for a second, outer ring road begins to emerge. This is vicious cycle that cities get trapped in, but with deliberate planning, this can support the growth of cities that are brimming at the seams.

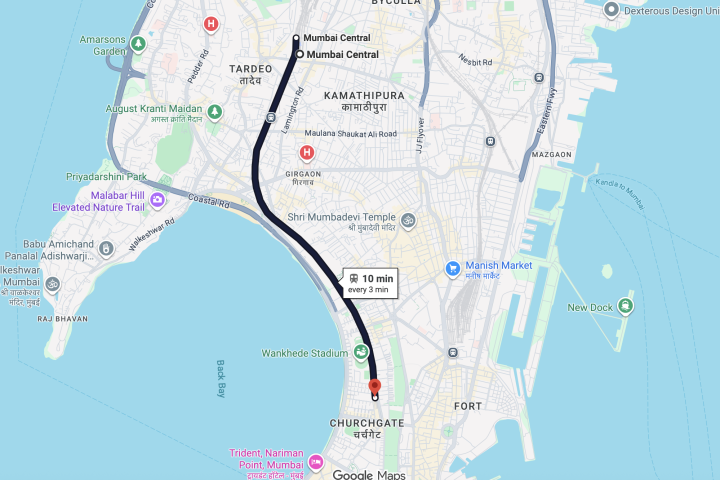

The primary reason for building a ring road is to redirect highway traffic away from the city, allowing trucks and other vehicles to bypass the urban core entirely, thereby reducing congestion within the city.

This strategy is not new – in fact, it has been implemented worldwide since the 1960s, when rising vehicular density within cities created the need for such roads. And it kind of works.

Although ring roads serve their intended purpose, they introduce new challenges if transport planning and land use are not integrated into their design and implementation.

Take Beijing for example – it has 7 ring roads. However, since last few years, sustainability steps have been incorporated into the design – that means strict land-use controls, zoning, preserving green space, connecting these with Metro and Bus Rapid Transit, cycling, walking infra etc..

These were necessary to halt uncontrollable urban sprawl that ring roads can create. Similar restrictions have been imposed in London’s outer ring road – the M25, where it mostly lies within or near London’s Green Belt, a policy area established to prevent urban sprawl around the capital.

In India’s context, the ring roads are a result of other reasons as well:

1. Commute within the city has slowed down due to increase in number of private vehicles. So, ring roads provide quick connectivity between diametrically opposite points of a city.

2. Administrators often see ring roads as a way to spur real estate growth around the city, especially in the absence of comprehensive Transit-Oriented Development plans. Speculation around upcoming ring roads often leads to the purchase of large land parcels by insiders who are already aware of the plans.

The other thing is that we are building ring roads primarily to shift vehicular traffic, rather than pursuing holistic urban planning. Eventually, you begin to see high-rise apartments and unplanned private layouts emerging, many of which lack basic infrastructure and mobility options.

Some cities have developed ring roads mainly to support commercial and office spaces, which often results in severe traffic jams. Thousands of employees funnel through narrow entry and exit points onto the ring road, which clearly lacks adequate mass transit options and walkability.

Retrofitting a mass transit is often harder and comes with its own set of challenges including strong resistance from private vehicle users. Our city administrators and politicians are often too sensitive to handle any push back, especially from the urban wealthy.

In some cities, the situation is so dire that areas along the ring road lack community spaces such as parks, and suffer from inadequate drainage and sewer systems that are unable to handle the load. Additionally, drinking water is often supplied by tankers.

When ring roads become integrated into the city and neighborhoods develop around them, they often create social barriers between communities. To get to the other side, you either have to take a car, make a long U-turn, or risk your life or a limb trying to cross the road.

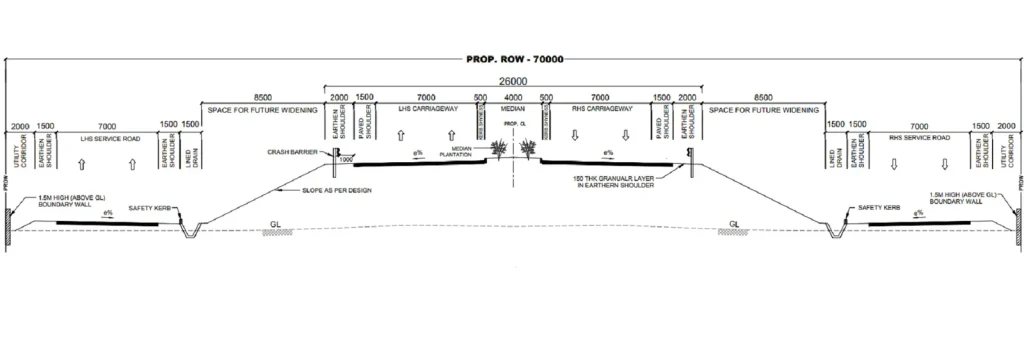

Then there is design issue. These ring roads are often constructed following highway specifications, which typically offer little consideration for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users. In some cases, these roads fall outside the jurisdiction of the city municipality, so maintenance and upgrades are much harder.

These long, straight roads often encourage careless speeding, partly because they lack the strict enforcement common in the city’s core areas. The accident outcome is pretty much expected. Hyderabad’s Outer Ring Road for instance has seen over 30 deaths in 2025 and 369 in the past five years.

We also tend to treat all ring roads the same, even though some have become integral parts of the city’s road network. For example, Vienna’s inner ring road “Ringstrasse” is a 5.3 km circular grand boulevard that serves as a ring road around the historic city center. It has great land use, is well connected with transit options, and supports alternative forms of mobility like e-scooters and cycles.

Another aspect that we are missing is repurposing ring roads as zone boundaries. Cities like Moscow, Paris, and Beijing use ring roads as boundaries to administer and manage transit fares. Inner zones, like in Paris, can be designated as low emission zones where only EVs, cycling, walking and public transit are allowed.

Ultimately, cities should not build ring roads simply because traffic has increased; the cause might be different, such as a rise in car ownership within the city. Regulating private vehicle ownership and promoting alternative sustainable modes of transport may in fact be sufficient.