Large cities are steamrolling through Metro construction, with more lines being added every few months. Delhi/NCR is currently constructing more than 100 km, while Mumbai and Bengaluru have about 130 km and 80 km in progress, respectively.

However, this is not the case for smaller cities that opted for a Metro; most have only a line or two, which barely impacts overall urban mobility. Meanwhile, dozens of other cities are lining up at the Central Ministry, hoping their own Metro projects will be greenlit. These cities, with populations between 10 and 25 lakh, urgently need solutions to combat traffic congestion that worsens every year.

Flawed reasoning

What politicians have unfortunately done to the Metro system is turn it into a status symbol, while anything less is deemed sub-par. Very little consideration is given to population density, alternative modes, land use, or the cost of construction and operations — all of which are precursors to any Metro line.

The latest economic survey from the central government notes, “Metro rail,

flyovers, and expressways are built without parallel land-use reform, housing supply, or skill clustering. Transport systems are asked to compensate for planning failures rather than enable density. The result is capital-intensive infrastructure with sub-optimal economic returns.”

Another rationale is the belief that constructing Metro lines in underdeveloped areas will swiftly bridge regional disparities. However, this ‘supply-led’ approach rarely succeeds, as evidenced by several low-ridership cities where demand has failed to meet expectations.

Unclear guidelines

Following a general rule of thumb, cities with populations under 10 lakh typically do not meet the threshold for a Metro, while those exceeding 25 lakh may qualify. While European standards suggest that any city over one million inhabitants warrants a Metro system, India’s economic context is different. Unlike European nations that only have to fund two or three major hubs, India has between 60 and 75 cities with populations exceeding one million. At our current stage of development, we simply lack the economic resources to provide a full Metro network for every one of them.

Chandigarh, Nashik, Coimbatore etc.. are examples of cities unable to decide how to deliver a mass transit system for their residents — dropping other alternative modes and instead looking for a full-fledged Metro system. Systra’s 2018 comprehensive mobility report for Chandigarh recommended trams, deeming them suitable due to the city’s heritage and population density. However, the report was discarded, and the city has since been eyeing a Metro.

Nashik has spent years wavering between Metro Neo (trolley bus) and Metro Lite (light rail), but policy ambiguity and funding constraints from both the state and central governments have pushed these projects to the back burner. Recently, MahaMetro deemed a conventional Metro system feasible for two lines with a projected PPHPD of 20,000; however, the Central Government remained unconvinced and rejected the proposal.

Delays, uncertainty, and confusion over viability are compounding the woes. As reported for Bhopal, the cost escalation alone, nearly Rs 3,267 crore, is equivalent to building nine or ten new Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS) corridors.

For cities with only one or two Metro lines, the impact on urban mobility remains minimal. This is because these lines are often treated as isolated projects rather than essential pieces of a larger ‘mobility puzzle.’ True success requires seamless coordination with local bodies to bridge the ‘first- and last-mile’ gap, alongside a dedicated focus on making stations accessible through improved cycling and pedestrian infrastructure.

For example, Finland’s capital Helsinki operates just 1 metro line(the other being branch of it), and integrates the stations with 13 bus trunk routes and trams. Feeder buses also play a key role. Many bus routes terminate at metro stations and connect residential or low-density areas to the Metro line. The city, of course, has plans to expand its Metro network, but the point is that even with just a few lines, the most important aspect is how well it integrates with other modes.

If you look at China, the trajectory of building Metro systems in its cities is somewhat similar to ours. But they established clear guidelines from the very beginning. While their 2003 approval policy was relatively generous, it nonetheless established firm rules for project eligibility. In 2018, it was further tightened as debt rose and smaller cities did not really justify the cost of building one. The new policy tripled the requirements.

1. The city had to generate fiscal revenue ≥ 10 billion yuan.

2. The GDP of city ≥ 100 billion yuan.

3. Urban population ≥ 3 million.

To this day, India lacks definitive guidelines; consequently, Metro systems are often approved or rejected arbitrarily based on political influence. This ambiguity is not confined to conventional Metro projects—it extends to Metro Neo, Metro Lite, and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems as well.

So what should these cities do, and how can central government work with states to drastically improve the situation?

Here are a few things I propose:

Establish guidelines

The Central Government must establish transparent and clear criteria for determining which cities qualify for a Metro system. By doing so, cities would be encouraged to compete with one another to surpass the necessary benchmarks for constructing and operating a large-scale network. Like China, it has to be a factor of economic output and population of the city.

In the meantime, cities that cannot meet these requirements can focus on alternative modes of transport—such as Metro Lite or BRT— which are more cost-effective and better suited to addressing existing mobility gaps.

Late last year, the central government rejected Metro system for Coimbatore and Madurai arguing that the two cities lack the mandated 2-million population according to the 2011 census. If we go by the same metric, Agra had a population of just 15 lakhs, and yet Metro was approved.

Focus on Comprehensive Mobility

States must conduct independent, comprehensive mobility studies for their cities to accurately gauge current transit conditions and plan for future urban growth.

Often, studies are conducted by the same agencies that want to build the Metro (like a Metro Rail Corporation), which can lead to conflict of interest or inflated ridership projections.

The flawed mindset among planners is that fixing mobility and congestion requires massive infrastructure projects and investment. Consequently, a disproportionate share of funding and resources is funneled into one or two modes—often involving single-mode expansions, flyovers, or other car-centric projects. Furthermore, the presence of multiple administrative bodies that fail to communicate leads to a piecemeal approach rather than a cohesive, collective strategy.

Prioritize buses

Cities must increase their bus fleet sizes to meet MoHUA-recommended standards. Nashik, for example, requires at least 1,400 buses but currently operates only about 250, leaving a staggering deficit of 1,150 vehicles.

Furthermore, route rationalization is essential; transit paths must be redesigned based on a deep understanding of residents’ actual mobility patterns.

As per SRTU Fleet Handbook data, there were 47,650 buses in service as of 2024. Even if we have since added several thousand more, bringing the total to approximately 60,000, these numbers remain drastically low when compared to China, which operates roughly 7 to 8 lakh city buses.

The central government’s PM-eDrive and PM-eBus Sewa schemes are playing their part by consolidating requests from various State Transport Undertakings (STUs) and issuing single tenders under the Gross Cost Contract (GCC) model. This ensures collective bargaining power and lower operating costs for these agencies.

Yet, as reported, the rollout remains slow, and surprisingly, several state units have not even participated in the process. This leaves them stuck with prolonged tendering timelines and higher operating costs. Furthermore, some agencies lack any back-up tender plan entirely.

Reinstate Bus Rapid Transit corridors

The Central Government should reinstate funding for Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems, which has been largely absent since 2014. While maintenance was handed over to local municipalities, these bodies are often too underfunded and understaffed to manage anything beyond routine daily tasks. Reintroducing central funding would reinvigorate a system that is currently in a state of decay.

Although the Central and State governments have increased bus fleets in recent quarters, these vehicles remain stuck in congestion; without a dedicated ‘Right of Way’ on arterial roads, they cannot provide the speed or reliability needed to attract commuters.

In 2025 budget, the union govt announced the Urban Infrastructure Development Fund allocating 10,000 Cr exclusively for Tier 2 and 3 cities, but it lacked focus on public transport as it combined the initiative with Roads, Solid Waste Management, Parks etc.. Also, the fund hasn’t been operationalized yet(more than a year).

The economic survey of 2026 recommended a transport network plan for all such cities, but it remains to be seen how it is executed on the ground. Without a dedicated fund for projects like BRT, the money may got to other big ticket projects.

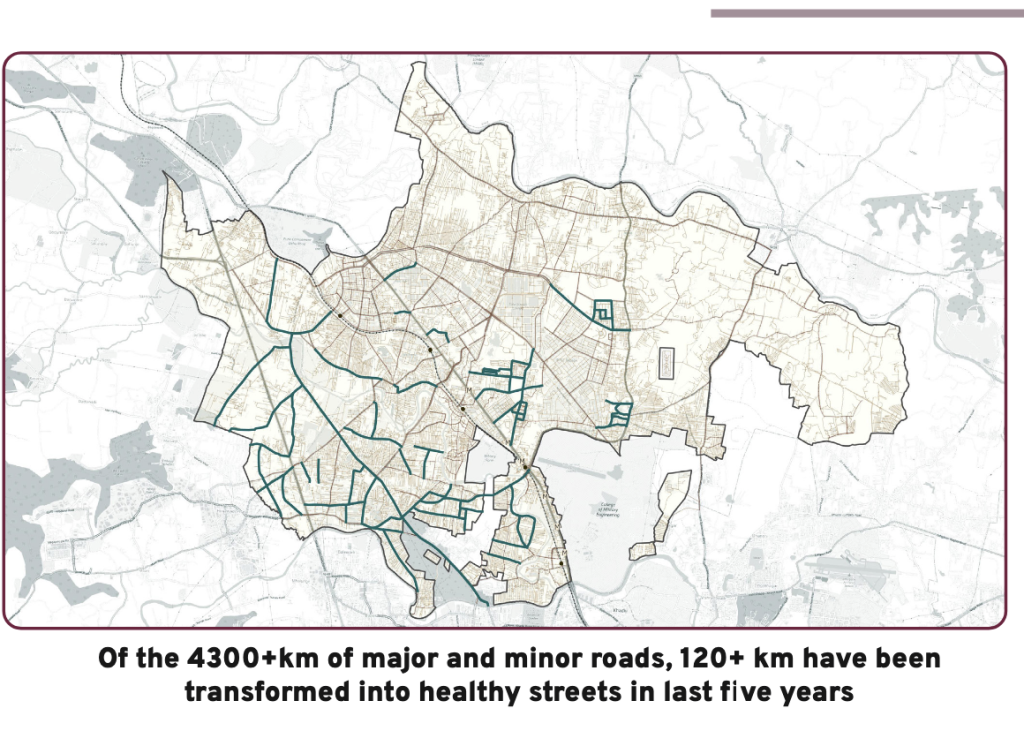

Fix Cycling and Walking infrastructure

These cities must prioritize non-motorized transport by investing in dedicated infrastructure for cycling and walking. Given the relatively compact size of these cities, it should be treated as a primary mode of transport rather than a secondary one. By prioritizing these active modes, cities can naturally reduce the volume of motorized trips, easing congestion and lowering emissions.

Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation(PCMC) is embarking on the ambitious ‘Harit Setu’ project which aims to redesign roads for active mobility, and building green corridors exclusively for walking and cycling. Other cities need to do the same.

A major hurdle for municipalities to build these, is the chronic lack of funding, as building new infrastructure requires massive capital that tax revenue alone cannot cover. While municipal bonds were initially seen as a solution, most Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities lack both the necessary revenue streams and the specialized staff required to issue them successfully. In case of PCMC, the municipality has successfully raised Rs 200 crore through green municipal bonds, which will fund the ‘Harit Setu’ project.

To remediate this problem, the Central Government proposed an incentive of Rs 100 crore in the latest budget for any single bond issuance exceeding Rs 1,000 crore. This new measure complements the existing AMRUT scheme, which continues to incentivise smaller issuances of up to Rs 200 crore for small and medium towns.

Use land efficiently

A primary driver of urban congestion is inefficient land use; therefore, states must prioritize vertical growth and mixed-use development. Commuters rely on private vehicles largely because residential areas are disconnected from employment hubs.

To address this, governments should liberalize Floor Space Index (FSI) regulations, allowing for higher-density housing. By accommodating more residents in well-located apartments rather than allowing independent housing to sprawl beyond city limits, cities can reduce travel distances and improve overall livability.

The recent Union government’s economic survey was rather scathing in its remarks stating, “Metro rail, flyovers, and expressways are built without parallel land-use reform, housing supply, or skill clustering. Transport systems are asked to compensate for planning failures rather than enable density. The result is capital-intensive infrastructure with sub-optimal economic returns. Metro systems move people, but they do not always raise productivity because jobs, housing, and transport remain misaligned.”

Make in India scheme for Trams

What’s a bit contradictory with the recent policies is that the Central government is adopting Japan’s spatial policy for urban planning that mandates rail led growth in cities above 10 lakh population, but there is no alternative rail transit mode besides Metro system – like trams.

To accelerate the rollout of light rail or tram systems, I propose importing ‘ready-to-use’ units for the initial phases in the first few cities. Following this, a mandatory ‘Make in India’ clause should be implemented for subsequent orders—an approach successfully pioneered by the Delhi Metro. Originally, Delhi imported trainsets from Rotem (South Korea) and the Mitsubishi–Rotem consortium; today, however, most Indian metro coaches are manufactured domestically by BEML or Titagarh Rail Systems.

These initial imports are essential to ‘get the ball rolling.’ This strategy aligns with the 2025 government mandate requiring at least 75% domestic procurement for metro cars and 25% for key sub-systems and equipment.

Turkey, Brazil and Morocco are some of the countries that have demonstrated that this model works. Morocco, Casablanca Tramway and Rabat–Salé Tramway kicked off with fully imported units, but since then Alstom has been increasing localization of parts.

Turkish company Durmazlar took a slightly different approach where they started as supplier of tram parts, then went on to become a licensed builder, and then ultimately an OEM exporter.

States need to pay attention

Unequal development has caused many states to focus entirely on their capital cities, thereby ignoring smaller Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities in their transit plans.

Last year, Karnataka Minister Santosh Lad actively promoted Electric Rapid Transit (e-RT) project to improve connectivity between Hubballi and Dharwad. The proposal was sent to the state government which rejected the idea citing high costs. If successful in the pilot program, the e-RT would have paved the way for other cities in Karnataka.

Similarly, in Telangana, Warangal has highlighted discrimination, as the Metro was approved and expanded in Hyderabad while it received nothing.

State governments need to take mobility in these cities with utmost seriousness and offer alternative modes if current options are too expensive. They also need to set up dedicated funds, strengthen municipalities, and improve transport departments.

Closing thoughts

Tier 2 and 3 cities are next set of growth engines for India. The points outlined above represent only a few of the urgent fixes required to address the critical gaps in India’s urban mobility framework.

India’s medium and smaller cities deserve their rightful attention, as they currently appear to have been overlooked in the mass transit rollout. There is a risk that people in these smaller cities will migrate to Tier 1 cities due to better transit infrastructure there, creating further pressure on them.

And at this point of time, our country cannot afford that.