Metro coaches don’t come in the same size or shape, but choosing the right configuration to match demand can make a significant difference to both the system’s efficiency and the passenger experience.

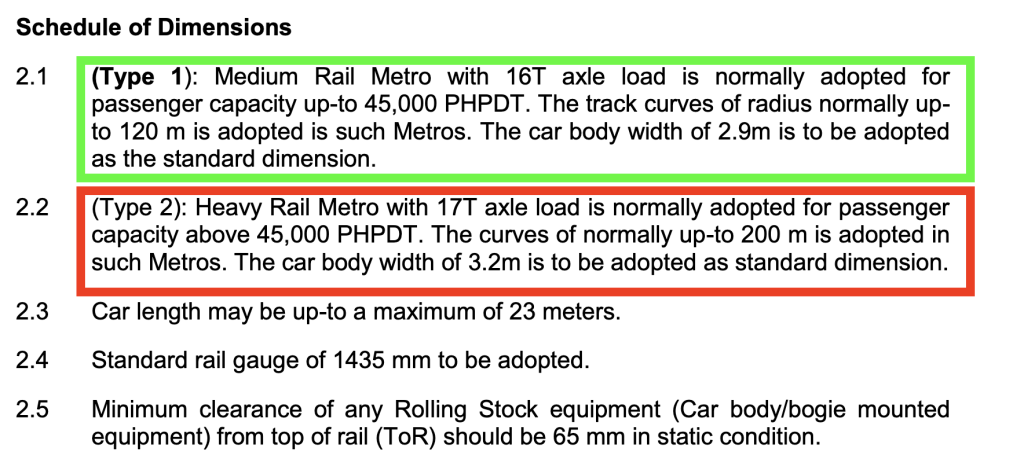

In 2017, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs released a rolling stock standardization document, recommending cities to choose between Type 1 and Type 2 coaches based on their specific needs.

The 2.9 meters is similar to some of the European metro standards, while 3.2 meters aligns more with heavy rail metros like in East Asia.

Cities like Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Chennai(and many others) opted for “Medium Rail Metro” specifications, with coach widths of around 2.9 meters, instead of the wider “Heavy Rail Metro” standards.

In contrast, some of the newer lines in Mumbai and Delhi follow “Heavy Rail Metro” specs even though they started with 2.9 meters on earlier lines.

The 3.2 meters wide coach can accommodate approximately 30-35 additional passengers more than the 2.9 meter one. If you multiply by a 6-car trainset, that’s roughly 180–200 extra passengers per train at peak load.

Over a decade, wider coaches could reduce the need for additional trains –sure, continuing with the current 2.9 meter configuration may simplify operations and maintenance, but wider train sets would ease crowding and carry significantly more passengers in a single run.

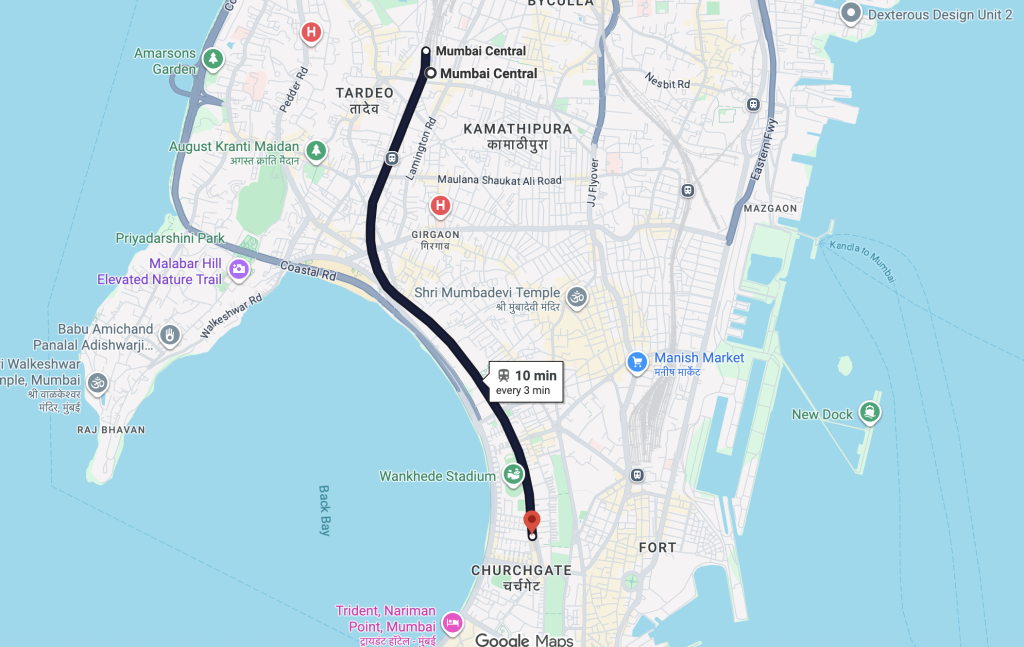

Let’s take a look around the neighborhood.

Singapore (MRT): core MRT rolling stock is 3.2 meter wide on major lines (North–South / East–West etc.), a “wide-profile” that supports higher per-train capacity.

Bangkok (MRT Blue line, etc.): the MRTA rolling stock used on core metro lines is approximately 3.12 m overall width.

China: mainland China commonly uses a three-type classification: Type A ≈ 3.0 m, Type B ≈ 2.8–2.9 m, Type C ≈ 2.6 m (used on lighter / lower-capacity lines). Cities pick A/B/C depending on expected line capacity. Tier 1 cities often pick Type A for denser routes.

But, it seems our Tier 1 cities blindly opted for medium capacity without taking into consideration future demand.

Now, a 2.9 meter width is acceptable if trains run with higher frequency, and have additional coaches to compensate for the reduced capacity from the narrower design. But in reality, they’re operating with lower frequencies and fewer coaches than the system actually needs. Hyderabad operates just 3 coaches, and has no concrete plans yet to increase the length to at least 6 coaches. Frequency is also poor in all these cities, leaving the public underserved.

Now, the choice of coach width is often influenced by tunneling costs – wider coaches mean larger tunnels and higher expenses. However, it’s puzzling that even newer lines without tunnels have still opted for the 2.9-metre specification. Mumbai’s aqua line has significant amount of underground section, and chose 3.2 meter rakes, so the argument of costs can be set aside.

Upcoming BMRCL lines, such as the Blue and Red lines, should have opted for 3.2-metre-wide coaches, as they pass through dense IT corridors which are expected to see heavy ridership.

Moreover, these lines will eventually serve Kempegowda International Airport and the upcoming Hosur Airport, making higher capacity even more essential. The blue line in fact is fully elevated – largely straight section – so the choice of narrow body coach is questionable.

Smaller cities like Nagpur, Lucknow, Agra and so on, have rightly chosen the medium capacity design considering their population and ridership.

Can it be salvaged?

Tier-1 cities that have missed adopting the “Heavy Metro” standard should rethink their strategy in light of rapid urbanization and a constantly growing population.

As mentioned above, the best-case scenario is to increase train frequency to at least 3 minutes or less. CBTC signalling can actually support frequencies as low as 90 seconds, but achieving higher frequency requires additional train sets — a problem that has persisted for many years.

Then, making 6 coaches the standard on all lines would significantly increase capacity and help avoid overcrowding.

Additionally, the “Heavy Metro” specification should be part of the discussion for every new line. The high density of these cities easily supports wider rakes. New infrastructure should consider the width in their design and implementation.

If cities want to switch to wider coaches, it is best to implement them on new lines with separate stations and tracks, which will ensure there are no changes or disruptions on existing infrastructure.

The only caveat is that these broader coaches may require separate holding depots, or extensive changes to current infrastructure to accommodate them.

Difficult, but not impossible.