By 2005, traffic in Jaipur was on the rise, prompting both the central and state governments to address the issue urgently. In 2006, the central government introduced the National Urban Transport Policy for cities to adopt, and Jaipur was eager to implement it.

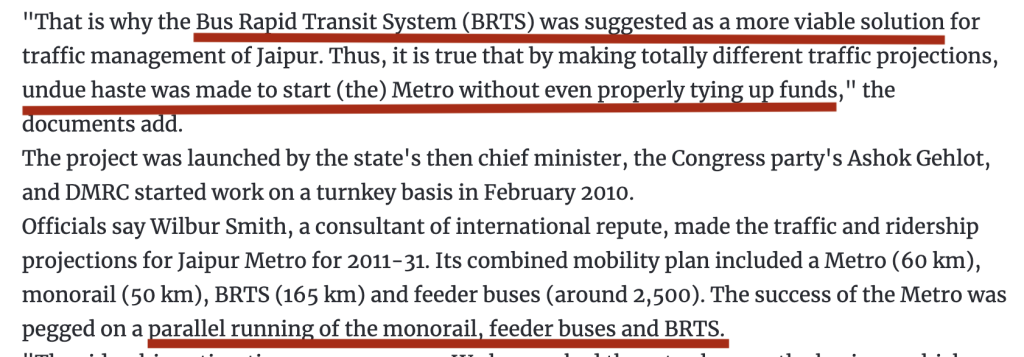

In 2010, city administrators hired a private consultant to develop a comprehensive mobility plan to reduce traffic congestion and prepare the city for future growth.

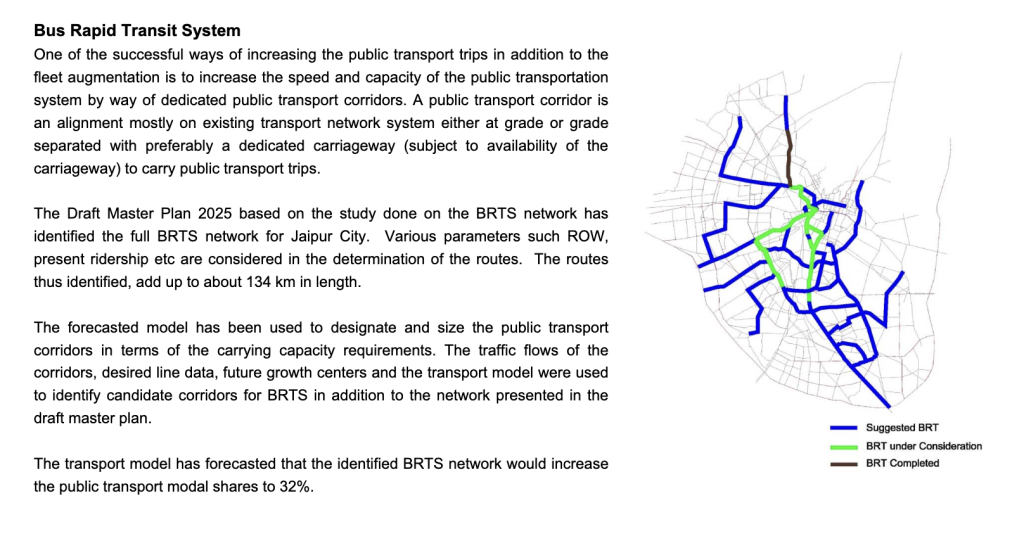

The report recommended several measures, with one of the key solutions being the introduction of a full-fledged BRTS system, as bus ridership in the city was found to be quite low.

The report also proposed redesigning major roads to include cycle lanes and footpaths, recognizing their importance in ensuring safe and convenient access to bus stops. Without these improvements, the BRTS was destined to fail.

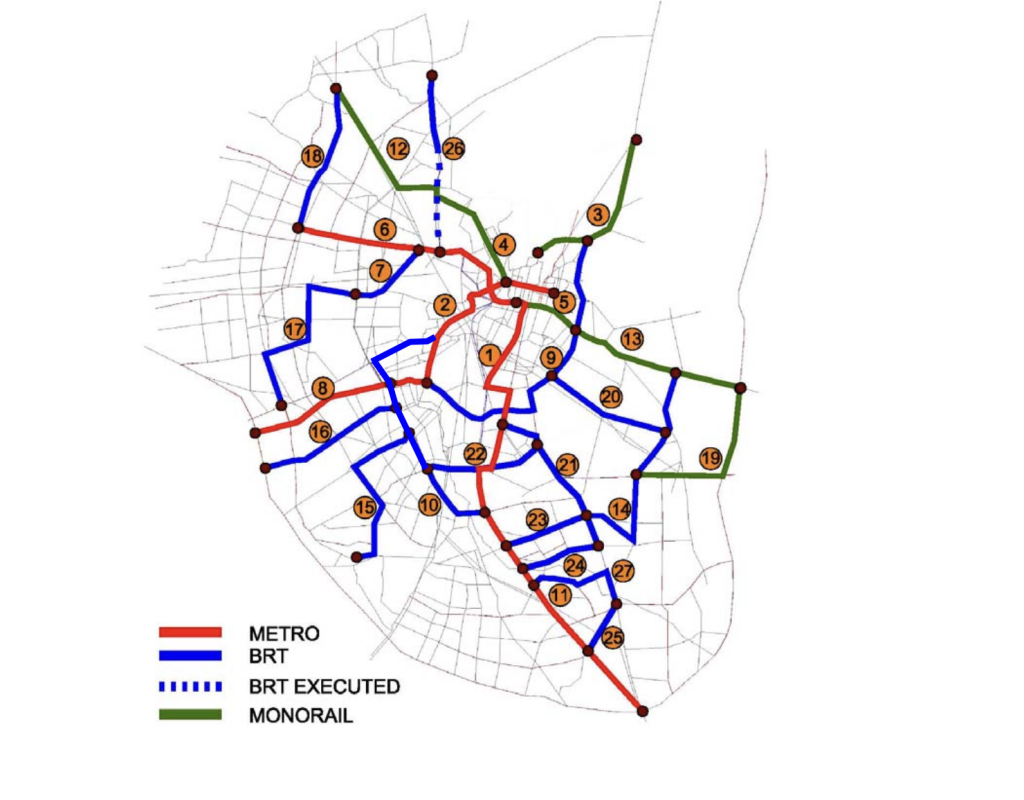

This is what mobility was expected to look like by 2031(according to report). Bulk of the load would still be carried by BRTS, while Metro and Monorail/Tram would further augment the capacity. And these three needed to be neatly integrated. That’s essential, the report noted.

The report uses the words ‘Monorail’ and ‘Tram’ interchangeably. It leaves the decision of choosing one or the other to the authorities.

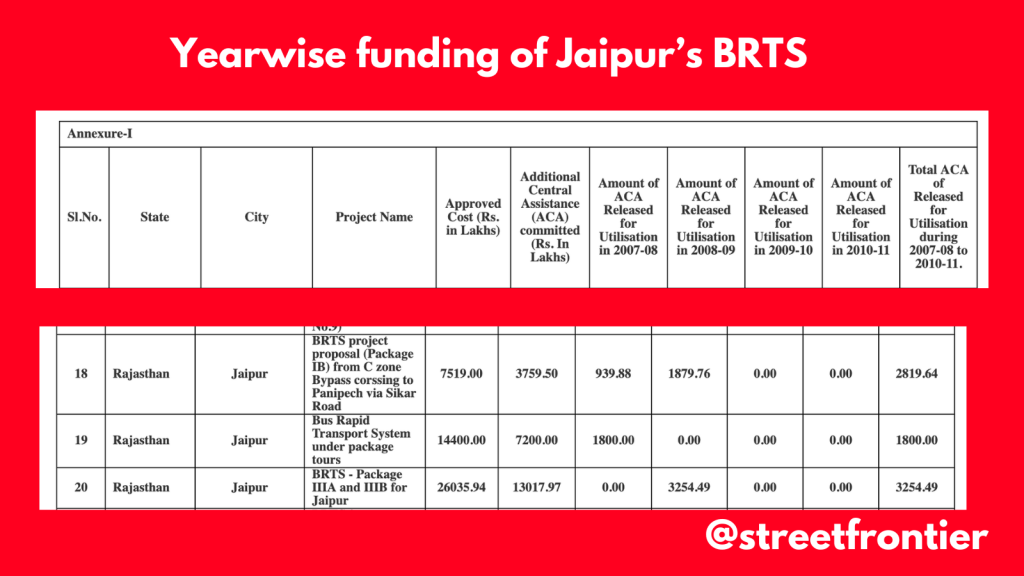

Jaipur was one of many Indian cities that implemented BRTS during this period, with funding provided through the central government’s ‘Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM)’ scheme.

After 2014, with the change in the central government, funding for BRTS systems dwindled as priorities shifted towards the Metro. BRTS could only succeed with consistent funding from the central government. Under JNNURM, however, it had been progressing well with frequent bus additions and infrastructure upgrades.

The implementation was planned in three phases, but it never progressed beyond phase 1. As a result, the system operated at only a third of its intended length, with no central government funding to sustain or expand it. It never reached its full capacity or potential.

Between 2007 and 2011, Rajasthan received significant financial support for its BRTS project, with funding allocated to be disbursed over consecutive years. Below is a screenshot showing the released funding amounts (in lakhs).

Jaipur Metro was approved in 2010 with initial length of 9.25 km and an amount of 1250 Crores was approved for this Stage 1 project.

By 2011, the BRTS project in Jaipur was progressing at a snail’s pace, frustrating the central government, which withheld funding for the next two phases until the issues were addressed. At this point, the High Court intervened and criticized the administration for the delays.

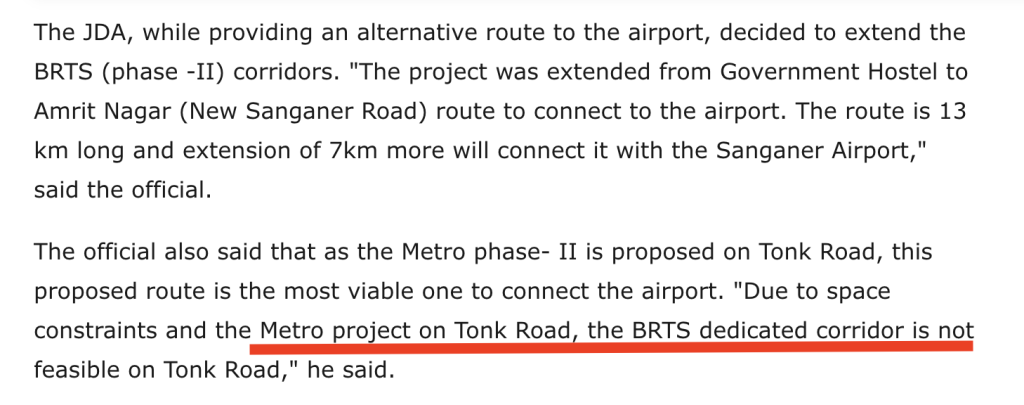

In 2013, while struggling to secure funds for its three phases, the Jaipur Development Authority began planning Phase 4 of the BRTS project and sought assistance from the central government, requesting 174 crores in funding.

Later in 2013, the first Metro line was flagged for trial, costing the government Rs 10,000 crore to build. For comparison, the cost of the BRTS line was significantly lower. By 2014, Metro had started to eat BRTS’s lunch.

Here is a news item reported in the same year which highlights this.

Meanwhile, by 2016, Jaipur Metro Rail Corp (JMRC) was playing its own little games to convince others that the Metro was working and that the future looked bright.

In 2018, the CAG criticized state authorities for hastily implementing the Metro system when there was no real need for it. It stated that it was struggling to meet operational expenses due to decreasing ridership.

This aligns perfectly with the timeline set by the first Comprehensive Mobility Plan, which I mentioned above.

The CAG report also noted that E. Sreedharan of Delhi Metro Rail Corporation did not see the need for a Metro system during their meeting. However, the same report contradicted his recent views, stating that in August 2009, Sreedharan had deemed Jaipur suitable for the Metro.

This 2018 report from CAG is scathing in its remarks. Read the highlighted lines below.

As losses continued to mount, the residents of the city were made to bear the burden of its exorbitant operating costs. Additional taxes and surcharges were levied on the public to sustain this white elephant.

While the Metro was severely underperforming, with no clear future in sight, the BRTS was quietly being dismantled. Under investment in this bus transport system started to show.

The network was facing multiple issues that rendered it ineffective:

1. Lack of low floor buses.

2. Sections of BRTS were defunct.

3. Municipality not paying any attention to it.

4. No buses on some stretches.

5. No integration with Jaipur Metro.

By 2020, the BRTS had become just another lane filled with private vehicles. This led to an increase in accidents, and some residents even called for its removal.

However, mobility experts had a different view. They argued that removing the BRTS wouldn’t solve traffic congestion; in fact, it would make it worse.

According to them, buses carried approximately 1.8 lakh people/day. Metro in comparison, just carried 20 thousand/day.

They further pointed out that the administration had made no serious attempt to make the BRTS efficient and effective.

But in 2021, the BRTS got support from unexpected quarters. While state govt was keen on shutting it down, Jaipur Metro authorities proposed Trolley buses to be run on the BRTS corridor. However, this idea eventually fizzled out.

The new central government, led by the BJP, offered no support to the BRTS system. Instead, it demanded the return of its funding with interest if the project was scrapped, as half of the funding had come from central government coffers.

On February 19, 2025, it was announced that the BRTS would be fully dismantled and replaced by a Metro system.

The project would be executed by the newly formed Rajasthan Metro Railway Corporation (RMRC), a joint venture between the Centre and the state.

This was the final nail in the coffin for Jaipur’s BRTS system.